TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets

(A more general overview of my research program can be found here.)

Motivation

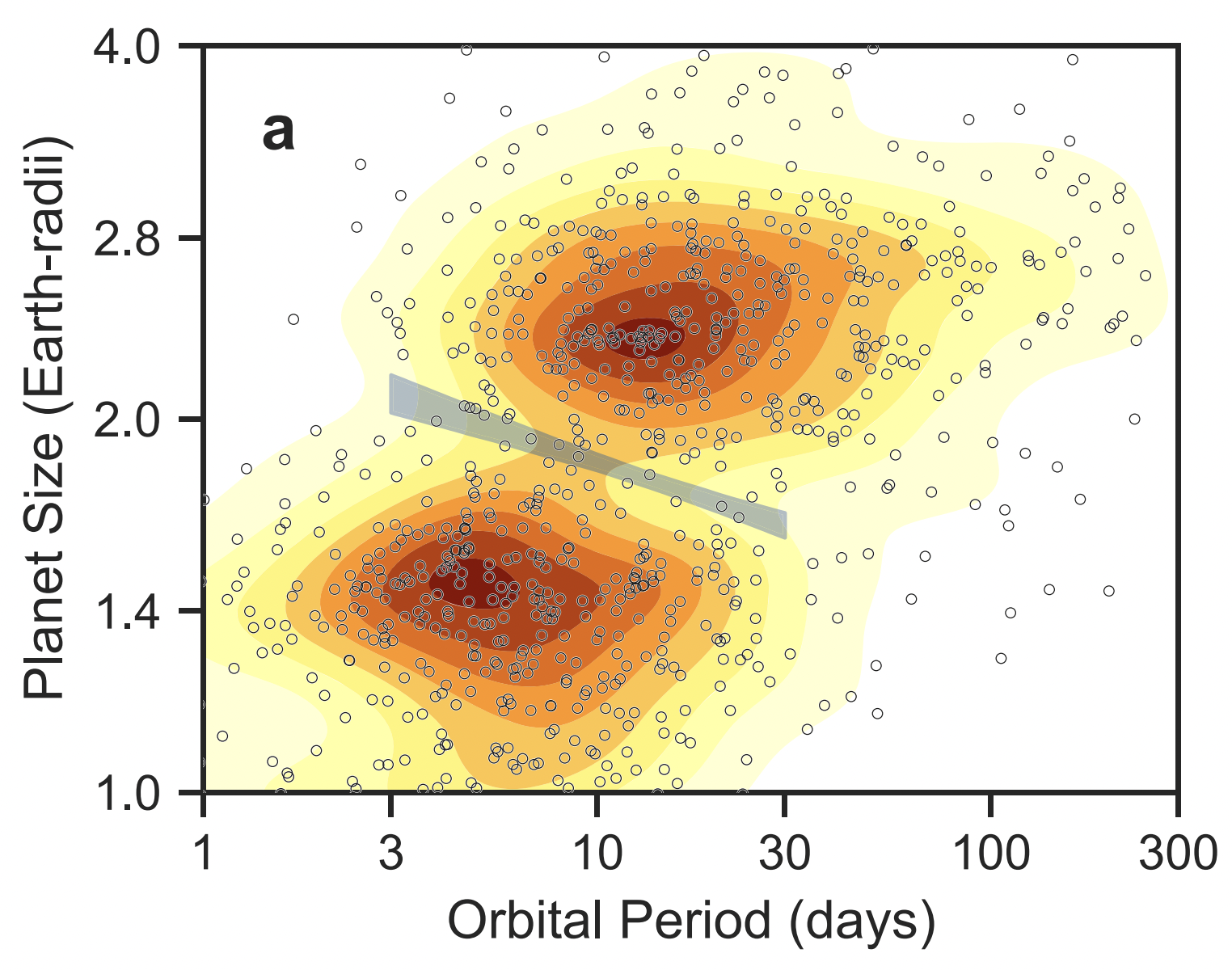

From their formation, planets have the potential to migrate, thermally contract, and/or experience atmospheric losses, all on timescales where there are few observational constraints. Understanding these formation pathways and how they give rise to demographic features in the mature exoplanet population comprise some of the most pressing question in the exoplanet field. The newly discovered planet radius valley is an excellent example (figure to the right). The marked decline in the exoplanet occurrence rate at ∼1.8 Earth radii, is thought to separate rocky super-Earths from gaseous sub-Neptunes. Its origin has been proposed to result from atmospheric loss; either externally, driven by photoevaporation from the host star, or internally, driven by the thermal release of the planet’s core. Both theories independently reproduce the field-age population, but operate on difference time scales. The characterization of young planets provides the avenue to directly test the relative contributions of each process.

From their formation, planets have the potential to migrate, thermally contract, and/or experience atmospheric losses, all on timescales where there are few observational constraints. Understanding these formation pathways and how they give rise to demographic features in the mature exoplanet population comprise some of the most pressing question in the exoplanet field. The newly discovered planet radius valley is an excellent example (figure to the right). The marked decline in the exoplanet occurrence rate at ∼1.8 Earth radii, is thought to separate rocky super-Earths from gaseous sub-Neptunes. Its origin has been proposed to result from atmospheric loss; either externally, driven by photoevaporation from the host star, or internally, driven by the thermal release of the planet’s core. Both theories independently reproduce the field-age population, but operate on difference time scales. The characterization of young planets provides the avenue to directly test the relative contributions of each process.

THYME

The TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets Collaboration is focused on discovering and characterizing young planetary systems. We seek to construct a population of young planets and establish benchmark system to test planet evolution theory. We mine the light curves of young stars, primarily with TESS but also with Kepler and K2, to search for transits. As of Fall 2022 we have discovered 15 planets in 9 systems with ages less than 400 Myr. A list of our publications can be found below.

THYME V and the FriendFinder

I have contributed to many of the THYME papers, but I was the lead author of THYME V. This was our first paper on a planetary system that was not already known as a member of an established association. We usually stick to stars in known associations because you get the age of the system for free from the previous work in the literature characterizing the association. In this game, a precise age is as important as the planet itself. Placing a precise age requires a coeval ensemble of stars, as I describe below. So this paper had two components, a study of the planet itself, an inflated sub-Neptune, and a study of the host star’s siblings. The latter provided the motivation to develop a new tool to find these sibling candidates, which we call the FriendFinder.

A link to the peer-reviewed paper can be found here.

The Planet: HD 110082 b

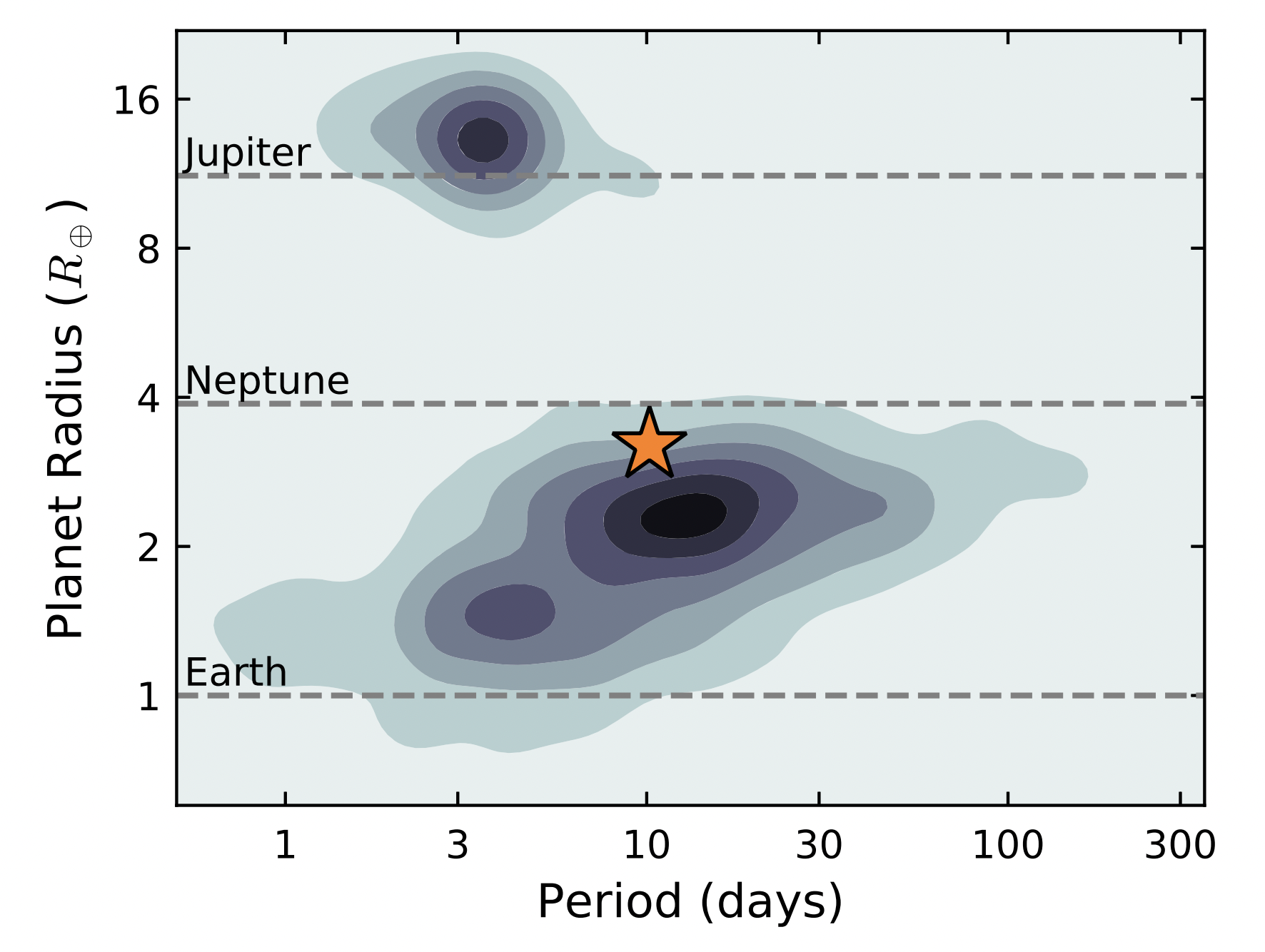

Hosted by a 1.2 solar mass star, HD 110082 is a 3.2 Earth radius planet orbiting on a 10.2 day period. While its radius makes it a sub-Neptune, it is larger than the field-age sub-Neptune population, as the Figure below depicts. At an age of 250 Myr (see below), we expect HD 110082 b to be actively losing a significant portion of its atmosphere, and as such, should sit above field-age systems. One system alone does not tell us what is driving its radial evolution (e.g., photoevaporation vs core-drive mass loss), but it is a step toward building a population that will address this question.

Hosted by a 1.2 solar mass star, HD 110082 is a 3.2 Earth radius planet orbiting on a 10.2 day period. While its radius makes it a sub-Neptune, it is larger than the field-age sub-Neptune population, as the Figure below depicts. At an age of 250 Myr (see below), we expect HD 110082 b to be actively losing a significant portion of its atmosphere, and as such, should sit above field-age systems. One system alone does not tell us what is driving its radial evolution (e.g., photoevaporation vs core-drive mass loss), but it is a step toward building a population that will address this question.

The Association: The FriendFinder and MELANGE-1

Measuring the age of a star with the precision required to make it a “benchmark” requires an ensemble of coeval stars (i.e., a collection of stars that are the same age – siblings). Popular age diagnostics (gyrochronology, Lithium abundance, isochrone fitting) only provide age-dating leverage for certain types of stars at certain ages, and each diagnostic on its own has significant uncertainty even if you’re in its sweet spot. This is a common problem we face. We often find planet hosts that appear young (rapid rotation, high Lithium abundance), but they are not part of a known association. Luckily, stars form in groups and, for a while, that collection of stars will share a common motion through the Galaxy.

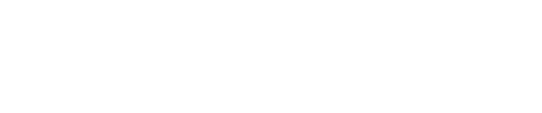

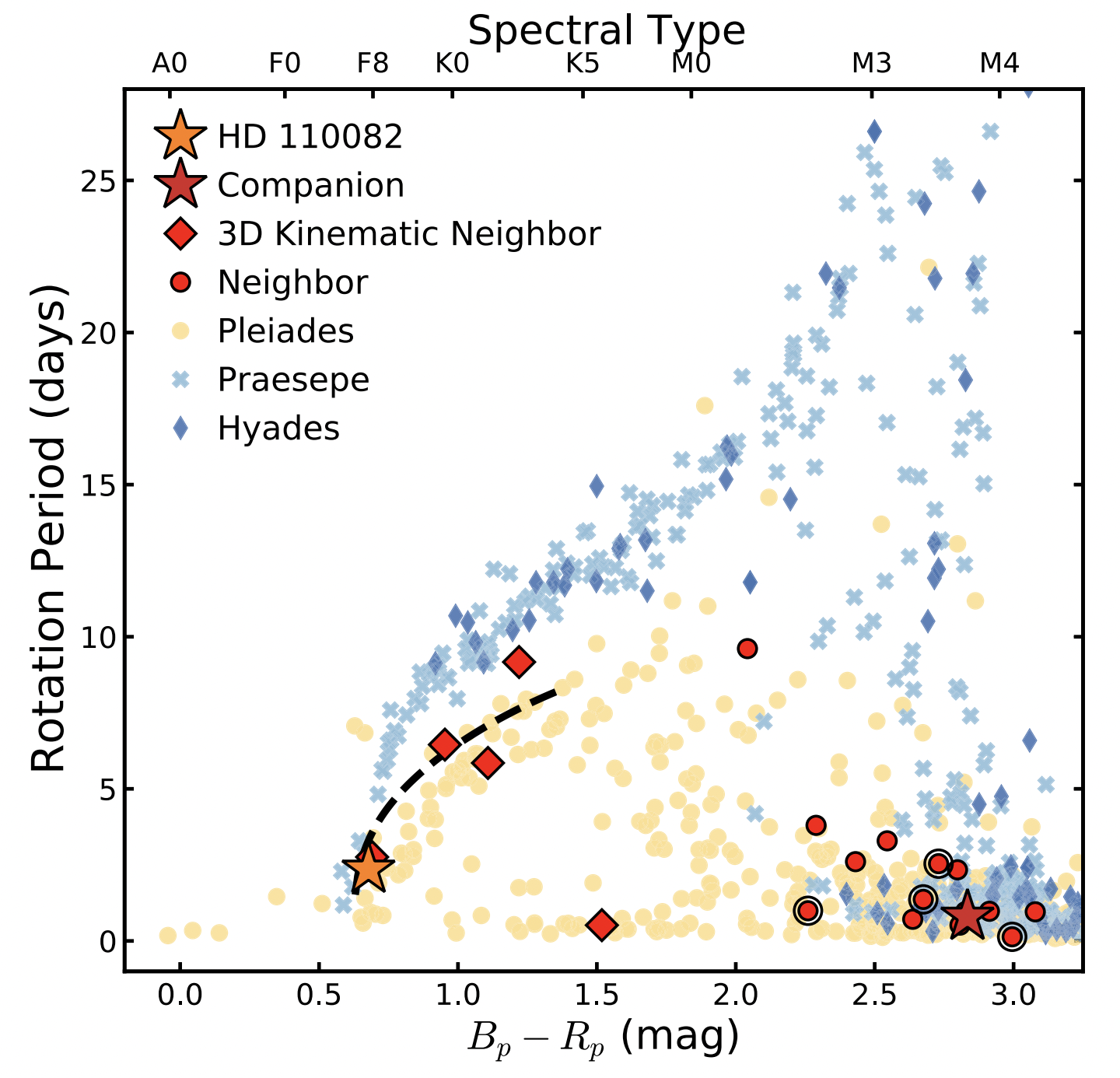

At first glance, HD 110082 appeared to be part of the 40 Myr Octans association. If true, our work would have been done for us, but a deeper dive suggested HD 110082 was older than 40 Myr. In order to precisely measure the age of HD 110082, and its planet, we developed a tool called the FriendFinder to identify HD 110082’s siblings. The FriendFinder uses Gaia astrometry to identify stars that are co-moving, co-spatial, and co-distant with our planet host. Those candidates are then queried across various astronomical catalogs to identify signatures of youth (IR excess, X-ray luminosity). From this list we selected a handful of high-probability siblings for ground-based spectroscopic followup and measured their rotation periods from TESS. With these measurements we made comparisons with established cluster sequences, as shown in the figures below.

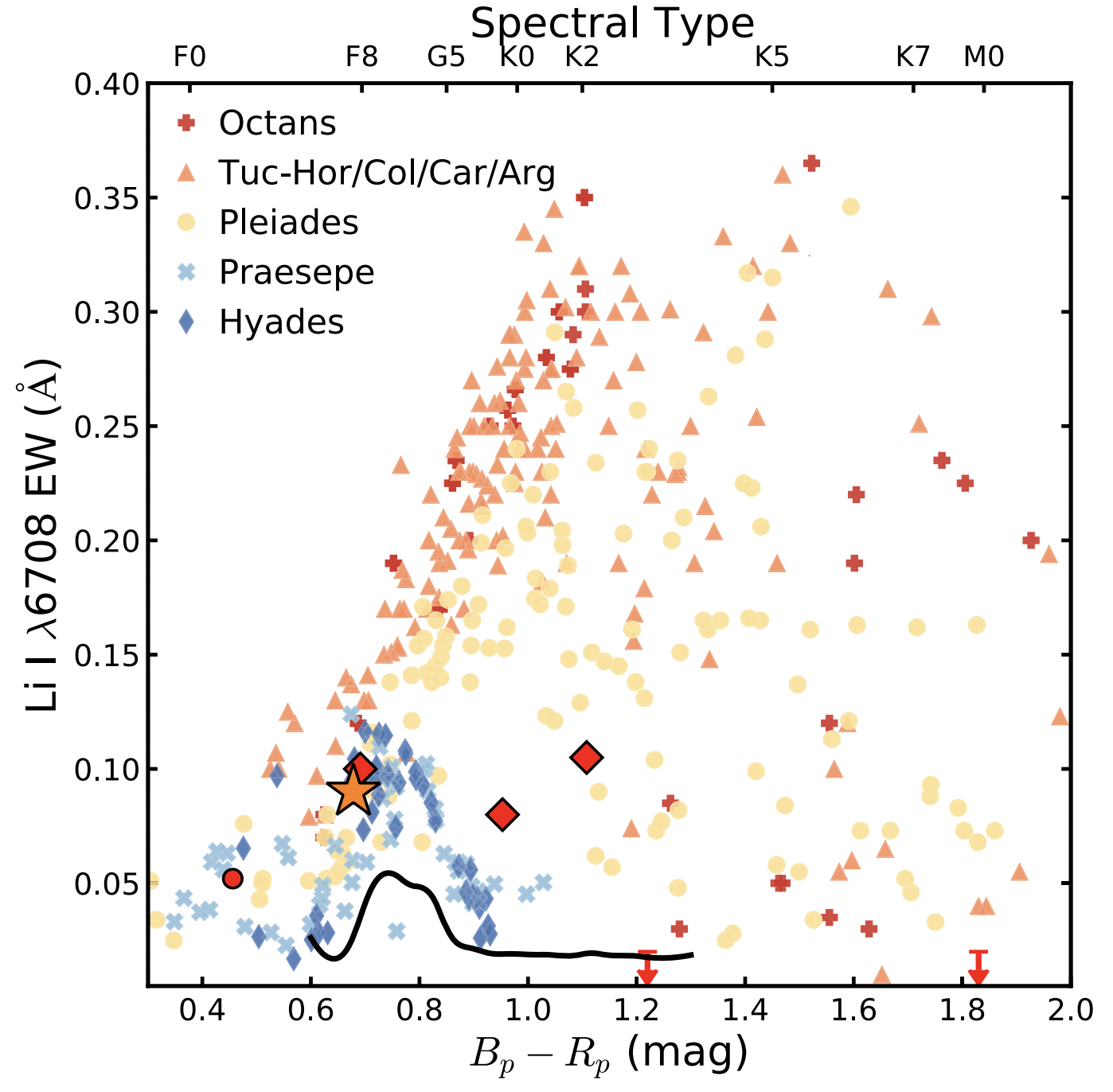

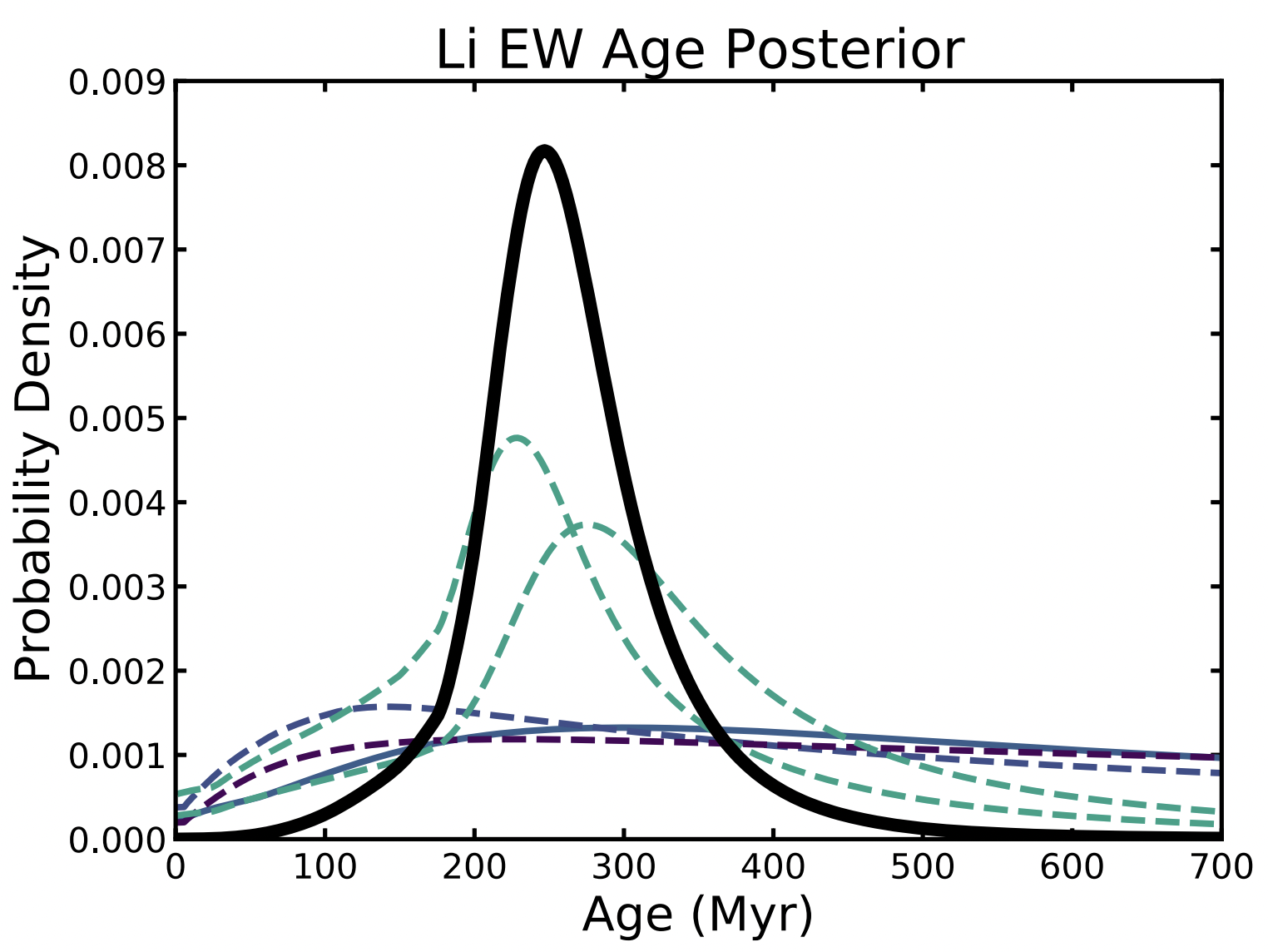

Comparing these sequences, it is clear that this collection of stars is older than the Pleiades (120 Myr) and younger than the Hyades (700 Myr). To make this more quantitative, we used a gyrochronology relation and a Lithium-age relation to make age posteriors for each star (colored lines in the figure below) and for the entire ensemble (black lines).

With only a handful the stars, the agreement between these methods is striking. We did indeed find a collection of coeval stars! Using these, we determined the age of the system to be 250 +/- 70 Myr. We coined the collection of stars found using our new technique MELANGE-1. This method stops short of establishing MELANGE-1 a traditional association, that would require much more followup, which is beyond the scope of this nominal planet paper. For the science at hand, we need an age, and this tool allows us to measure one. This approach had gained traction in the field and 6 different planetary systems have been established as benchmarks since 2021 (as of Fall 2022), which I’ve included below.

The FriendFinder can be downloaded here.

THYME Publications (as of Fall 2022):

- Wood, M., Mann, A., Barber, M., Bush, J., Kraus, A., Tofflemire, B., et al. (31 co-authors), 2022, AJ, submitted

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME) IX: a 27 Myr extended population of Lower-Centaurus Crux with a transiting two-planet system - Barber, M., Mann, A., Johnathan, B., Tofflemire, B., et al. (including 7 co-authors) 2022, AJ, 164, 88,

Transit Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME). VIII. A Pleiades-age Association Harboring Two Transiting Planetary Systems from Kepler - ADS - Newton, E., Rampalli, R., Kraus, A., et al. (including Tofflemire and 36 co-authors) 2022, AJ, 164, 115

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME). VII. Membership, Rotation, and Lithium in the Young Cluster Group-X and a New Young Exoplanet - ADS - Mann, A., Wood, M., Schmidt, S., et al. (including Tofflemire and 47 co-authors) 2022, AJ, 163, 156

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME) VI: an 11 Myr giant planet transiting a very low-mass star in Lower Centaurus Crux - ADS - Tofflemire, B., Rizzuto, A., Newton, E., Kraus, A. et al. (26 co-authors) 2021, AJ, 161, 171T

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME) V: A Sub-Neptune Transiting a Young Star in a Newly Discovered 250 Myr Association - ADS - Newton, E., Mann, A., Kraus, A., et al. (including Tofflemire, B. and 49 co-authors) 2021, AJ, 161, 65N

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME). IV. Three Small Planets Orbiting a 120 Myr Old Star in the Pisces-Eridanus Stream - ADS - Mann, A., Johnson, M., Vanderburg, A., et al. 2020, AJ, 160, 179

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME). III. A Two-planet System in the 400 Myr Ursa Major Group - ADS - Rizzuto, A., Newton, E., Mann, A., Tofflemire, B et al. (13 co-authors) 2020, AJ, 160, 33R

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME). II. A 17 Myr Old Transiting Hot Jupiter in the Sco-Cen Association - ADS - Newton, E., Mann, A., Tofflemire, B., et al. 2019, ApJ, 880L, 17N

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME) I: A Planet in the 45 Myr Tucana-Horologium Association - ADS

Publications using the FriendFinder (as of Fall 2022):

- Sun, Q., Wang, S., Mann, A., Tofflemire, B., et al. (2 co-authors) 2022, AJ, submitted

The Sub-Neptune TOI-251b in MELANGE-5 - a Newly Discovered ~200 Myr Young Stellar Association - Johnson, M., David, T., Petigura, E., et al. 2022, AJ, 163, 247

An Aligned Orbit for the Young Planet V1298 Tau b - ADS - Franson, K., Bowler, B., Brandt, T., et al. 2022, AJ, 163, 50

Dynamical Mass of the Young Substellar Companion HD 984 B - ADS - Barber, M., Mann, A., Johnathan, B., Tofflemire, B., et al. (including 7 co-authors) 2022, AJ, 164, 88,

Transit Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME). VIII. A Pleiades-age Association Harboring Two Transiting Planetary Systems from Kepler - ADS - Newton, E., Rampalli, R., Kraus, A., et al. (including Tofflemire and 36 co-authors) 2022, AJ, 164, 115

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME). VII. Membership, Rotation, and Lithium in the Young Cluster Group-X and a New Young Exoplanet - ADS - Mann, A., Wood, M., Schmidt, S., et al. (including Tofflemire and 47 co-authors) 2022, AJ, 163, 156

TESS Hunt for Young and Maturing Exoplanets (THYME) VI: an 11 Myr giant planet transiting a very low-mass star in Lower Centaurus Crux - ADS